Introduction

Sexual violence in America remains a systemic social problem but excessive prison sentences do not address the root causes nor do they necessarily repair harm or bolster accountability. The misdirection of resources toward extreme punishment does little to prevent sexual violence.1

“What we really want is no more victims…So, how can we get there? Locking them up forever, labeling them, and not allowing them community support doesn’t work.Patty Wetterling, Co-Founder of the Jacob Wetterling Resource Center2

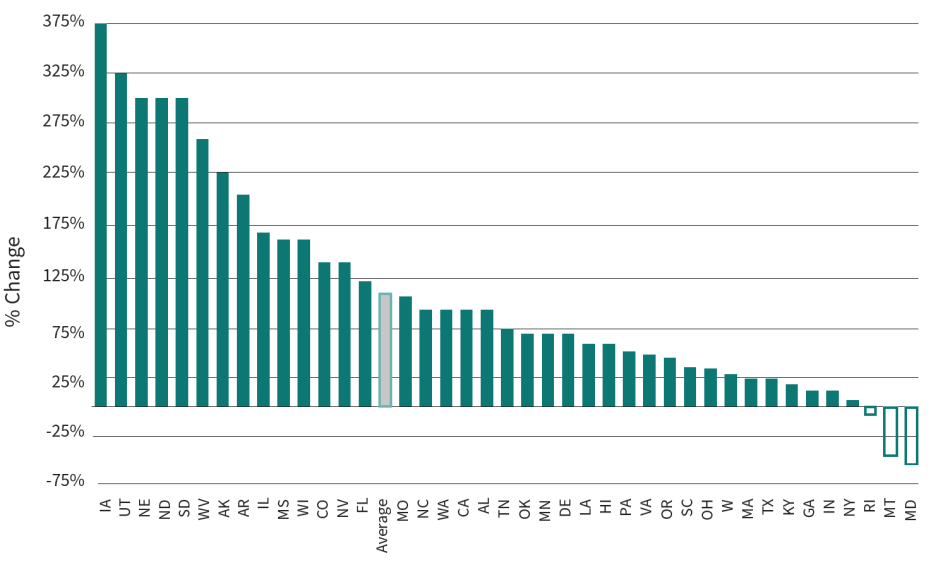

Since the 1990s, individuals convicted of sex crimes or sex offenses, which we call crimes of a sexual nature (CSN), have been subjected to an increased use of incarceration and longer sentences.3 They on average serve a greater percentage of their prison sentence compared to those sentenced for other crimes classified as violent, such as murder.4 The first federal law was also passed establishing state sex offense registries in 1994, the Jacob Wetterling Act.5

This escalation in punishment severity and community surveillance occurred alongside two opposing long-term trends. First, recidivism rates for CSN in the United States have declined by roughly 45% since the 1970s.6 This drop started well before the implementation of public registration and notification, implying that the lifelong punishment approach was not responsible for this decline. Second, based on roughly three decades of nationally representative U.S. criminal victimization data (1993-2021), the number of rape and sexual assault victimizations decreased by approximately 65%.7 Yet, reactions to CSN continue to evoke failed policies of the past – statutorily increasing minimum and maximum sentences and requiring more time served before release – major contributors to mass incarceration.8

This brief uses the term “crimes of a sexual nature” (CSN) to describe what are legally defined as “sex crimes” or “sex offenses.” While we do use similar terms interchangeably in this brief, The Sentencing Project recommends the use of “crimes of a sexual nature” to minimize labeling effects and potential cognitive bias.

Patty Wetterling, who once lobbied for sex offense registration after the abduction of her son, is now a vocal critic of it and many other sex crime laws. She reminds us that flawed laws and policies should be challenged, revisited, and changed. With this backdrop, this brief highlights misconceptions around crimes of a sexual nature that contribute to the rise in imprisonment and lengthening of sentences.9 It provides a set of recommendations including the following:

- Rely on established evidence about CSN and those who commit it to inform policy responses rather than fear-driven misinformation.

- Prioritize investments in prevention and intervention programming that works to reduce CSN and treat the underlying causes of CSN.

- End mandatory prison sentences for CSN convictions, including mandatory minimums and two- and three-strike laws. This category of crime includes a broad range of criminalized behavior such as consensual sex between youth to forcible rape. Each of these behaviors carries with it varying levels of criminal culpability. Sanctions should not be “one size fits all.”

- Resist the impulse to leverage CSN as a bargaining tool in order to pass sentencing reforms.